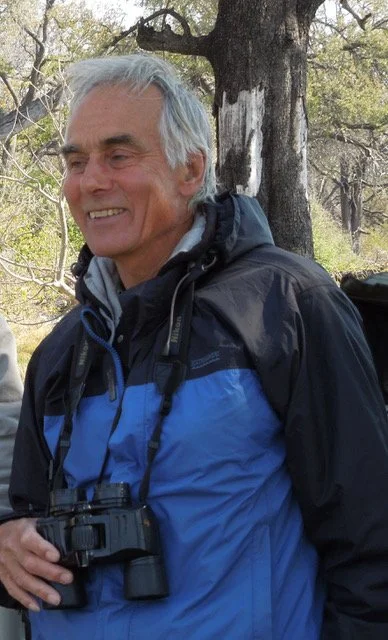

John Ogden, Founding Trustee and Aotea Science Advisor (Killara, Oruawharo, Aotea)

Interview with BARRY SCOTT

John Ogden was the founding Chair of AGBET and Science Advisor for Windy Hill Sanctuary and OME. He is the author of Birds of Aotea, a twenty year study of the island’s avifauna, and a regular contributor to Environmental News. He was formerly Associate Professor of Ecology at the University of Auckland and has had a home on Aotea since 1990.

So, what brought you to Barrier in the first place? What was the attraction with this island that has led to you spending so much time and eventually living here?

Well, we'd rented a bach down on the Waikato coast and really enjoyed having longish weekends away whenever we could. But there was not the opportunity to buy land at that site so we started looking around at places in northern New Zealand for somewhere that we would enjoy going to.

The Barrier became important simply because it was easy to get to from our home in Parnell. You just simply went down the road, got on the ferry, and your holiday began. Initially we camped but then decided we would buy somewhere. So, it was all just a family holiday thing. It wasn't so much about the ecology or the biodiversity.

And did the property at Awana just fall out of that search?

Sort of. We stayed at a house on Ocean View Road for a while and then heard Malcolm McDougall had a place for sale at Awana Bay. We liked it straight away. So, there wasn't a lot of looking around, really. It was one of the first houses we saw. We kept coming here for long holidays, and eventually became residents on the island.

Was it a slow transition?

Yes, initially our visits were just university holiday breaks and whenever we could. Then both Jenni and I went part-time at the university spending half the year over here and the other half back at the university. And they were really great years because it was such a nice environment to be living and working. I kept in regular contact by internet or telephone with the students I was supervising. And I just enjoyed it. My teaching commitments came in the winter half of the year. So we were able to go back just before the start of the second term. We always arrived back relaxed and enthusiastic to teach so it was really quite a good mixture.

And the ecology projects, I guess they just grew out of your time here and the observations you made on the island ecology?

Yes, many projects did grow out of that, but it was also the mix of colleagues I had at that time with complementary knowledge and skills. The structure on the Tamaki campus at the time was very open. I had a volcanologist just immediately opposite me, who I saw all the time. I've always been interested in the history of landscapes and related things so it was great to have people in geography with similar scientific interests. So I got to mix with many like-minded colleagues with an interest in natural history at a landscape level, something I had started to pursue earlier when we lived in Australia. I was interested in the way in which the landscape had changed and the way the vegetation had changed, and recruited students to work on these projects. Sometimes they came over to Barrier to carry out field work with me.

Where did you do your PhD research?

I first did a MSc, working in tropical rain forest in the lowlands of what is now Guyana in South America (1963), relating forest composition to topography and soil types. Very little was known about plant community structure in the tropics at that time. My PhD (1966) was on ‘reproductive strategy’ and ‘energy allocation’ in some herbaceous plants. Both projects were supervised from The University of Wales in Bangor, where I also did my undergraduate degree. I was fortunate to have excellent mentors.

So while your area of expertise is forest ecology you also seem to have had a great interest in birds, especially those on Aotea?

Yes my academic expertise is mainly in forest ecology and dendrochronology, but I have been interested in birds ever since I was a boy. I was a member of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in Britain when I was 11 years old. Even at that stage, I was taking part in their bird surveys. They set up various surveys, such as counting nests in rookeries. And it didn't matter how old you were. You just had to count nests in trees or something like that. So I was involved in numerical stuff from really quite an early age. In my early teens, I was doing that kind of stuff as a hobby.

And so it's been an ongoing hobby?

Yes it has principally been a hobby but I have published a number of papers on birds. At the Research Station on Heron Island On the Great Barrier Reef I did census work on noddy terns and shearwaters, while Jenni tagged turtles. On Aotea, I started making observations and recording them in my diaries which became a great resource 30 years later for putting together Birds of Aotea for the 20th anniversary of AGBET. It’s an interest I maintain to this day. In some ways it's a little bit like what we might now call citizen science..

John and Evie MacMahon carrying out Aotea Bird Count on Hirakimata 2022 (Credit: Kate Waterhouse)

And what about your fascination with dead birds? I know you have records of dead birds you have found on the island.

Well, that started when we had a holiday place down near Te Akau, in the Waikato, which I mentioned earlier. When we were there alternate weekends I would keep fit by running along the beach where I saw dead birds washed up. So I would stop and examine them to try and figure out what species they were. It was quite amazing how many different species I would find. There were many different species of petrels and shearwaters, which made me realise how many birds were present around our coastline. I got quite fascinated by the whole thing. And that's where it started. And, of course, nowadays I just can't walk on a beach without finding a dead bird and wanting to know what it is.

Presumably from time to time you would find rare birds?

Yes. A few years ago Lotte McIntyre drew my attention to a specimen on the beach at Medlands, which I identified as a tropical bird – White-tailed tropicbird. Very few of those birds had been recorded in New Zealand, and nearly all as dead birds. So, yes, that was quite an interesting observation. And occasionally you get birds that have died quite recently. So they're kind of fresh enabling you to have a very close look at them. I keep records of all these finds.

Together with a few others you were involved in the formation of the Great Barrier Island Environmental Trust. So what brought the group of you together to start this Trust?

I think there was just general concern about how the island was changing. We were starting to realise just how serious rats were in terms of their impact on bird numbers. Judy Gilbert led discussions on this together with Don Armitage, David Spier, Tony Bouzaid and myself. We were all concerned about what was happening to the land and ocean ecosystems of Aotea, and the impact of people, and introduced pests. With a background in forest ecology I was particularly interested in forest loss and changes in forest structure. Initially, there was a strong interest on marine things, especially from Don, who had an interest in marine reserves. At the time DoC came forward with a proposal for a large marine reserve around Rakitu, but there were many in the community who did not support that proposal because of the perceived impact on fishing, so in the end the proposal ground to a halt. As you will be aware 20 years later there are still no marine protected areas around Aotea, and none included in the current Hauraki Gulf/Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill that is still working its way through parliament. I think the value of marine reserves, at least on the Barrier, was at the time not widely understood. With no desire to be caught up in this controversy we agreed as a Trust in those early days to put our effort into rodent control and ultimate elimination, to protect the terrestrial environment. So the Trust focused its efforts on rodents. But even that was challenging, with strong opposition by some on the island to the use of toxins, supported strongly by the editor of the Barrier Bulletin at the time. So we just kept our heads down and got on with our environmental work, putting a strong emphasis on public education through such vehicles as the Environmental News and reports.

So looking at the Trust now, do you think it's come a long way and in good health?

I think the general environment on the Barrier has changed dramatically with regard to conservation issues. And part of that has to do with the Trust. Part of it's just to do with the general trends that have occurred throughout New Zealand over that time. There has been a general increase in awareness of the impact of rats and predators generally. So there's been a big change. Whether or not the Trust itself has changed, I don't feel I'm particularly in a position to comment on. I do think it's rather sad that the issue of total eradication of rats from the Barrier, is still low-key. No-one seems to talk about it. They talk about control, getting numbers down. But the actual discussion of total elimination seems to be still in the too-hard basket.

And it has been for 20-odd years. When I interviewed Judy Gilbert, she had similar comments.

I think when she started trapping at Windy Hill, her expectation was that in her lifetime the Barrier would become rat-free. Indeed the Trust had a strategic plan working to rat elimination in ten years. But it's still got a long way to go. And we look at what's happening at Rakiura, and the ambitious plans for making Rakiura, Chatham Islands and Auckland Island predator free. It’s disappointing to see Barrier is well down on the list now. Even Waiheke, I think, is steaming ahead. I think the momentum on Waiheke will be quite interesting to watch. With so many rat-free islands in the Gulf, Aotea’s rats become a risk to other places.

But at least we now have Rakitu rodent-free.

Yes it is great to have Rakitu rodent free, but disappointing DOC has not clearly communicated that none of the concern raised about the impact on the marine life has come to pass. As you know, there's been no measurable or known effects on the marine environment, just as has been the case in other places where this has been done. So, really, you know, the Department of Conservation could come back now and said, look, the detractors made all this huge fuss about using poison, and there are no effects. It’s also disappointing that there were no adequate baseline studies done before and after. So we have no idea how well Rakitu's recovering at present. Putting weka back onto the Island after getting rid of the rats was in my view a mistake which becomes more difficult to correct with every passing year.

I sense that there have been some big changes in attitudes toward the environment since Rakitu.

Yes I think so, it certainly looks better. The general environment on the Barrier is totally different to what it was 20 years ago. Importantly, the Trust needs to keep on top of that and just keep pushing. There is certainly a groundswell for change. A good example is what has happened here in Medlands with the restoration of the Oruawharo swamp out the back and all the volunteers involved with that, the trap library and so forth. It's all about committed individuals and working together as a team.

Now switching to some of your studies on the island, John. I know you carried out studies on the swamp at Awana, on pāteke and New Zealand dotterels, and that really interesting study on the sediments of the Whangapoua estuary, which you wrote up for our last issue of Environmental News. I thought that study was really interesting.

Well, it has been interesting for me because the Barrier hadn't really been studied that much and I've been involved with palynological studies in swamps since my time at Australian National University when I was in the Department of Biogeography and Geomorphology, which was an acknowledged leader in that type of research in those days.

So you had a position at ANU for a while?

Yes. I was a research fellow there for five years (1974 – 1979). It was a very stimulating department with some really good people there at the time. Not long after I arrived in New Zealand in 1968 Jim Bowler discovered human bones (Mungo lady) around the now dry Lake Mungo in south-western New South Wales. These bones were found to be between 40,000 – 42,000 years old, making them the oldest human remains then known anywhere in Australia. So the whole knowledge of Aboriginal people there was being transformed.

There were also some very important studies on past environments at that time. Peter Kershaw focused on reconstruction of past natural and human modified landscapes, largely through the analysis of pollen. So this is how I learnt about palynology and was able to apply that knowledge to studies on the swamps on Barrier. Two key people involved in studies here were Mark Horrocks, a postdoc, and Yanbin Deng, a Chinese student, who carried out a PhD under my supervision. She was one of the better students I ever had. She learnt things very quickly and did a great job of analysing the pollen in the Whangapoua sediments. My role was to form the questions and find the sites at which the interesting questions could be answered.

John and Evie MacMahon carrying out Aotea Bird Count on Hirakimata 2022 (Credit: Kate Waterhouse)

Did you do pollen analysis of the swamp at Awana as well?

Yes, we did. And that was very interesting too, because that was the first place on the island where we found a very fine white ash layer, around 30 - 35 centimetres down in an otherwise almost black peat. And I knew that was strange. I discussed it with volcanologist, Brent Alloway, who identified it as volcanic ash (Kaharoa ash), from the Ōkataina Volcanic Centre, near Rotorua, just over 700 years ago, which was about the time of Māori arrival. This allowed us to date that sediment layer without using radiocarbon methods. The ash from this eruption drifted in an almost straight line northwards up the east coast of New Zealand, allowing sediments at many different places to be dated.

Did you see the same layer in Whangapoua?

No, that was part of the interest of that as well. The absence of ash there supports the other evidence that the estuary was full of seawater at the time. So the ash falling out onto the Whangapoua Lagoon, as it was at that time, was being continually stirred up by tides and seawater. So there is no ash layer there.

So at that time, 700 plus years ago, the lagoon was all full of water. It must have been quite satisfying for you, analysing those sediment layers, to see a signature of Māori arrival and then later, European arrival on the island, and the impact of those two?

Yes, it was. Obviously the European zone is distinctive because all of a sudden, you start seeing pollen from plants that come from Europe, such as plantains, willows and birch. It’s very distinctive. And the mark of Māori arrival is also very clear. In fact, it's even more distinctive in a way because it's marked by fire. Fire was the hallmark of Polynesian arrival throughout the Pacific. Heaven only knows why they burnt the forests, because they didn't farm and crop it like Europeans did. Māori probably cleared the land to make it easier to catch moa but also to encourage the growth of bracken which was an important food source. You see that increase in bracken pollen in the Whangapoua sediments. But also charcoal. Not lumps of it but a very fine sediment, that gets deposited and forms a very distinct layer that you often can't really see visually because it’s microscopic. But it is a signature of Māori arrival found throughout New Zealand, and in around 12 different cores from swamps on Aotea most of which have also been radiocarbon dated.

The European arrival horizon has frequently been lost as a consequence of later European activities. At Whangapoua, there is a story, and I think it's a true story, that way up the end of Mabey Road, which is all dry land now, there is a canoe buried in the sediments. When Burrell was putting in drains around 1967 his digger hit something fairly solid down there and he discovered that it was a canoe, which he rapidly covered up again. That small area is now a Māori reserve. The presence of a canoe so far inland is consistent with the lagoon being full of water at that time – 750-800 years ago – and fits with Māori oral history.

Switching gears a little bit, John, you were science advisor for many years for Windy Hill Sanctuary working with Judy Gilbert and her team. She has said on a number of occasions how valuable your contributions have been.

Well, Windy Hill, before my time, had employed somebody to organise and analyse bird counts so they could get some idea of how effective the trapping was over the years, whether the birds were increasing or not. So that was already set in place and I took over the analysis after Sam Ferreira, who organised it, had left. One of the first things I did was to cut down the amount of work they were doing. For example, I couldn't see why they were doing counts four times a year as they were just picking up seasonal changes. I also changed the methodology around transects and the like and wrote annual reports, which were very useful for their financial reporting and grant applications. I also tried to make the reports readable and interesting, to make the information more accessible but also to support their grant applications and future decision making. Eventually it reached the point where they had answered the key question as to whether the birds were doing better in the managed area than in the control area. There was absolutely no doubt that the trapping and toxin regime they had been using was benefiting the birds. There were more birds in the managed area than in the unmanaged control area. And so we decided that we would stop doing counts every year and reduce it to a five-year plan. That decision freed up resources for other studies on lizards and reptiles. They also implemented proper GPS mapping systems and started deploying cameras to monitor activities within the sanctuary. But Judy would say, and part of me agrees with her, that although they are doing all this stuff a lot better than they used to do, they're not actually killing any more rats!

Rakitu from Whangapoua (Credit: Kate Waterhouse)

You are also a science advisor for the Oruawharo Medlands Ecovision group.

Yes I have done some of the similar things I did for Windy Hill in analysing the data they were generating on rats trapped etc but I also wrote a report on the ecology of the dune system, and the Oruawharo swamp, which I think has been helpful. Early on I prepared a report on the biota and stratigraphy of the wetland to help with the restoration planning. It’s been my role, to try to get people to see what is there, why it's so valuable, and interesting. More recently, I have been involved in analysing data and writing up reports on an Australasian bittern survey and kākā count.

Just backtracking a little bit to Australia. You have spent a lot of time in Australia, going there every winter.

Yes, it stems from my five years there as a Research Fellow. The Department I was in had heaps of money and the head of department, another Yorkshireman, let people like me, as a research fellow, do what they wanted. Invariably, he would find the money I needed for my work. I was able to do all kinds of things. And I was working with world-class scientists. So I was able to tag on to their field trips and visit all sorts of really interesting places. I got to see a lot of Australia.

My strongest interest is in forest dynamics, so I wanted to look at movement of trees through altitude over time. Because obviously there's been such movement, if you go through glacial, interglacial cycles, there's been altitudinal migrations of tree species. And probably, independently of each other. It's not a case of the whole forest kind of moving, because all different species, of course, have different requirements. So they're probably independent movements. So the eco-system is getting continually rearranged, altitudinally and through time. And that was the kind of thing I wanted to work on.

So I went into the Brindabella Range near Canberra, where I spent quite a lot of time looking at the eucalypt forests, which have got a dozen species at different altitudes, and trying to design a project on one species. But the eucalypts are difficult. Some of the species are quite hard to tell apart. So in the end, I decided to look somewhere else. I went to Tasmania, to look at some of the conifers in the mountains there. I found the Athrotaxis genus to be really interesting. A core taken from one tree had nearly 1,000 rings on it. As the core didn’t reach the trunk centre the tree must have been close to 1,000 years old. Though the rings were narrow, they were clear, and variable, indicating sensitivity to climate change. At the time dendrochronology was just taking off in the USA, especially at the University of Tucson, which founded the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research. Two dendrochronologists from that Department visited ANU so I was able to learn a lot from them and introduce them to the perfect site and species to study past climatic variability from tree-ring evidence.

And from Australia you came to New Zealand?

No, my first academic position in New Zealand was at Massey University before I went to Australia. I was very interested in the dynamics of New Zealand forests, particularly the beech forests. Up to that time most of the studies were very descriptive – forest types, number of species and the like – no one had done anything on the dynamics of New Zealand forests and how they changed with time.

I went on a field trip into the Ruahines to Mount Colenso to look at beech regeneration, especially red beech, but also silver and mountain beech. I became fascinated by the fact that the seedlings of red beech were often restricted to fallen logs. This struck me as being very interesting, because it meant one generation dying was producing the ideal regeneration site for another generation. So it was almost a kind of altruistic concept. It really highlights why, if you wish to conserve a forest, you shouldn't remove the trees when they fall over. So we carried out experiments where we sowed seeds onto logs and onto other places and looked at survivorship. The survivorship was much better on the logs, and because beech reproduces periodically in a major way with mass seeding in mast years (every 5-6 years) the upshot of it was, that although the landscape is saturated with seeds, those that germinate on fallen beech logs survive better. If you look at the growth rings of the red beech, which germinated on the fallen logs of trees that created canopy gaps by their fall, the rings are very even, indicative of regular growth in a well-lit situation. Silver beech by comparison have wide variation in width of rings as they are much more shade tolerant and can survive as seedlings under other trees for 30-40 years.

John to finish up lets return to Barrier. I know you have also spent a lot of time snorkelling and free diving in the sea around Barrier but I don't know whether you've written up any studies on your observations or whether it was just recreational.

Well, relevant to the Barrier, I collected a lot of seaweeds. I got to know Mike Wilcox at the Auckland Museum who helped me identify many of those seaweeds. Initially I sent specimens from Aotea to the museum but with time learnt how to identify many of them myself. Identifying the red algae was the most difficult as there are hundreds of different species of them and they are mostly small. I still have quite a big collection of pressed seaweeds from Awana, which I'll show you some time.

That would be great. Thank you for your time. It’s quite extraordinary hearing about all the different ecology studies you have been involved in.