Lost treasures of Aotea: Ngā manu, the birds

Kate Waterhouse, with contributions from John Ogden and the 2010 Great Barrier Island State of the Environment Report.

(Environmental News #40)

Koreke/NZ quail (Coturnix novaezelandiae) was recorded on Aotea in 1868. Only a few years later the species was extinct. (Lithographic plate by CJ Hullmandel)

In 2010, the Great Barrier Island State of the Environment Report (1) found that of 82 species of bird known to have been present in 1868 (when the naturalist Hutton visited and made a list), 12 are known to have gone extinct here.

The species lost to the island since 1868 are shown in Table 1. The endemic koreke/NZ quail (Coturnix novaezelandiae) recorded on Aotea|Great Barrier Island by Hutton must have been some of the last individuals of the species, which became extinct (worldwide) about 1875.

Forest species have lost out

The birds lost since 1868 are mainly from forest habitats. In percentage terms, Aotea has lost 33% of its forest bird species.

The most recent birds to be lost from the island are the kōkako (Callaeas wilsoni), pōpokatea/whitehead (Mohoua albicilla), and probably titipounamu/rifleman (Acanthisitta chloris). Kōkako survived in the northern block, Te Paparahi, until 1996, when the last two male birds were caught by the Department of Conservation and taken to Hauturu/Little Barrier Island.

Whitehead persisted on Rakitu/Arid Island, after disappearing from the main island, until at least 1957. Despite intensive searching in 1981, none could be found. The tiny rifleman, New Zealand’s smallest bird, was reported (but not seen) in 1972 with occasional claims of sightings since then, including in 2008. The bird can be confused with the equally tiny grey warbler, or even silvereye. No experienced observer appears to have recorded rifleman since 1868, and they must be presumed extinct on the island.

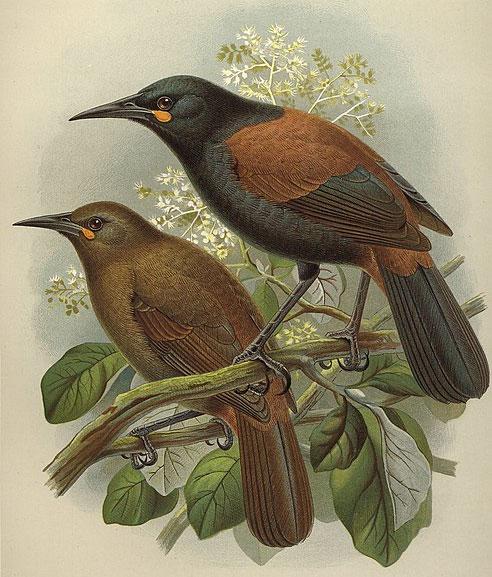

Saddleback/Ƥeke (Philesturnus rufusater) was once on Aotea but cannot coexist with rats. (Lithographic plate by JG Keulemans, Buller’s A history of the birds of New Zealand, 2nd ed, 1888)

Hutton’s record of the yellow‐crowned parakeet (Cyanoramphus auriceps) has been questioned by later writers. Kārearea/New Zealand falcon (Falco novaeseelandiae) may still be an occasional visitor from the Coromandel Peninsula, but it is not a permanent resident. Many of those species remaining, such as kereru (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae) and red‐ crowned parakeet/kakariki (Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae), are now in much smaller numbers. Hutton may have missed some species and knowledge of additional species that may have been present is likely to have been held by tangata whenua.

Marine and coastal species lost

In contrast to terrestrial habitats, marine and coastal environments have undergone less change. One coastal bird, tūturuatu/shore plover (Thinornis novaeseelandiae) has been lost, and other species including the New Zealand dotterel, banded dotterel, wrybill, Caspian tern, reef heron, red‐billed gull, black shag, little black shag, variable oystercatcher and even little blue penguin are at risk. Wetland species, Aotea has one large wetland, Kaitoke Swamp, also inhabited by rats, cats and pigs. Despite these pressures, the swamp is a key site for fernbirds in the Auckland region, and provides habitat for banded rails, spotless crake and occasional bittern.

Table 1: Bird species lost to Aotea|Great Barrier Island since 1868.

Extinct on Aotea: Notes

Koreke/New Zealand quail : Extinct nationally about 1875

Tūturuatu/shore plover: Since 1970s, only found on the Chatham Islands

Hihi/stitchbird : Last population on Hauturu until translocations to predator free islands from 1980s

Kōkako: Last birds removed to Hauturu in 1996

Saddleback/Ƥeke: Last natural population on Hen Island, now on predator free islands and in mainland sanctuaries

Pīpipi/brown creeper (Mohoua novaeseelandiae) Confined to the South Island

Pōpokatea/whitehead : Survived on Rakitu/Arid Island until at least 1957

Titipounamu/rifleman : Recent reports unconfirmed, probably extinct on Aotea

Kākāriki/yellow‐crowned parakeet: Small numbers of red‐crowned parakeet remain on Aotea (population size unknown)

Black‐bellied storm petrel (Fregetta tropica): Now breed only on predator‐free sub‐Antarctic islands

White‐headed petrel (Pterodroma lessonii): Now breed only on predator‐free sub‐Antarctic islands

Kārearea/NZ falcon: Not seen, potential visitor from Coromandel Peninsula

Korimako/bellbird (Anthornis melanura): Vagrant only, possible recent breeding attempts in Okiwi

Tomtit (Petroica macrocephala): Unclear if breeding on Hirakimata/Mt HobsonMost other wetlands, such as those formerly behind the dunes at Awana, Claris and Medlands, have been drained and their native birds have been replaced by the introduced generalists.

Pateke/brown teal (Anas chlorotis) are hanging on due to intensive management by the Department of Conservation at Okiwi, but pure strains of grey duck have been nearly eliminated by interbreeding with mallards.

Introduced bird species

Meanwhile, the island has gained numerous farmland birds, that have flooded into the new human‐made habitats.

Since Hutton’s time, 25 new species have found their way here, predominantly generalist European birds, such as sparrows, finches and starlings.

The shift in landscape, from the predominant forest habitats of Hutton’s visit, to the more open farmed landscape this century, has resulted in significant change in bird populations.

Table 2: Bird species, at risk nationally, and still present on Aotea|Great Barrier Island.

Nationally Vulnerable

Kākā

Bittern

Black petrel

Grey duck

New Zealand dotterel

Banded dotterel

Wrybill

Reef heron

Red billed gull

Caspian tern

Pied shag

New Zealand storm petrel

Pateke/brown teal

Weka (Rakitu, introduced)

Declining Nationally

Fernbird

New Zealand pipit

Variable oystercatcher

Pied oystercatcher

Pied stilt

White‐fronted tern

Blue penguin

Uncommon nationally

Long‐tailed cuckoo

Banded rail

Black shag

Little black shag

Little shag

Fluttering shearwater

Buller’s shearwater

Fairy prion

Diving petrel

It’s not all about the birds

Adam’s mistletoe ‐ this is the only image of the plant, painted by Fanny Osbourne, from a piece collected near Tryphena.

Plant species can also become extinct if their pollinator die out – as occurred in the early 1900s when bellbirds disappeared from Aotea, very probably due to the arrival of ship rats.

So too did Adam’s mistletoe disappear, which was specifically designed to be pollinated by bellbirds. The only image of this plant was painted by Fanny Osborne from a piece collected by her husband near Tryphena sometime around the end of the 19th century. In 1981, C. C Ogle (2), of the then New Zealand Wildlife Service, reported finding nine species of lizard, two species of frog, two species of Rhytidid molluscs, and eight species of introduced wild mammals during surveys undertaken on the island. Species found included the first known records from Aotea of spotless crake (Porzana tabuensis), Hochstetter's frog (Leiopelma hochstetteri), the mollusc Rhytida greenwoodi, as well as an unidentified lizard. The survey team noted that the 12 known lizard species represents the greatest variety of species on any island or comparable area of mainland, in New Zealand.

John Ogden goes further in the 2010 State of the Environment Report for Great Barrier Island. He notes that the island

‘...carries about a quarter of the New Zealand total for vascular plants, lichens and birds! These results indicate the extraordinary richness of the biota of this small Island, probably reflecting its position close to the boundary between the ‘sub‐tropical’ north and the temperate south of the North Island. The same appears to apply in the marine habitat, with at least 6 marine mammals, 160 species of marine fishes and 626 marine molluscs’. Ogden goes on to note that this richness of native species is even more remarkable when we consider that a significant number have probably been lost since European arrival. For example, species such as land snails may have been lost during the logging era, when extensive stream scouring and bush fires could have greatly reduced available habitat.

Can extinctions be prevented?

Without ongoing management, further bird species are likely to be lost from by a combination of predation by rats and feral cats, habitat degradation by pigs and feral cattle, and competition from introduced birds. Climate change, in particular extreme events and their effects, will also present challenges to the island’s species. It may take longer than on the mainland, but population trends are likely to continue to decline. Aotea residents and ratepayers, and all agencies involved with the island, place considerable value Aotea’s environment. However, community and agency responses generally do not match the nature and scale of the problems. There is no doubt that introduced plants, birds and mammals present risks for the remaining native species.

The pressures set in motion by the historic transformation of the island environment, especially the arrival of rodents, could still result in a wave of further extinctions, even of species currently considered relatively common and iconic.

We can all make a difference to the future of Aotea’s island species. Trap rats, be vigilant for introduced species, and help restore degraded environments. Their future is in our hands.

Notes

1 Ogden, J., Westbrooke, L. 2010. Great Barrier Island State of the Environment Report. Great Barrier Island Charitable Trust.

2 Ogle, C.C. 1981. Great Barrier Island Wildlife Survey. Tane 27, 1981. New Zealand Wildlife Service, Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington.