Little Windy Hill: The true story of a lost gecko, the women who loves birds and an audacious goal

by Kate Waterhouse

Judy Gilbert, QSM, did not start out to create one of New Zealand’s leading sanctuaries on a windswept corner of Aotea Great Barrier. Along with 16 other shareholders she bought 230 ha of retired farm in 1972 for the purpose of community and conservation.

The land would once have been covered in a mix of pohutukawa forest and coastal broadleaf forest – tall stands of taraire, kohekohe, pukatea with their huge buttressed roots, and pururi – laden with berries and flowers year round hosting flocks of kereru, kaka, kakariki, korimako (bellbird) and kokako.

Prior to the 1960s, much of the area was burnt and cleared of bush like most of the more accessible parts of the island. When the Windy Hill Company took it on, it was regenerating kanuka with some quite large pockets of original bush where the fires had jumped the gullies. Today, these pockets are oases full of loud tui, fat kereru and kaka and, if you’re lucky, North Island robins returned to the sanctuary in 2004, 2009 and 2012.

The dramatic impact of rat suppression on birds, geckos and insects

Figure 1: Five minute bird counts undertaken in 2013 by masters student Asher Cook, showing twice as many birds at Windy Hill compared to Te Paparahi, an area with relatively good habitat but no predator control.

Ecology consultant John Ogden is Windy Hill’s long time science advisor who, in 2008, took over the analysis of sanctuary bird counts, started in 2000. Over that time, a stark difference is evident in bird life (as well as the abundance of lizards, seedlings and invertebrates) between the sanctuary area and other unmanaged bush areas.

Figure 2: Number of weta found in each motel) from July 2006 to June 2007.

Seabirds once nested all over Aotea Great Barrier, and at Windy Hill some species have hung on. Seabird surveys have found active black petrel nests, three breeding areas along the cliffs of grey-faced petrel, and a nesting area of red billed gulls. Cooks petrel are frequently seen, although no nests have been found, yet.

But the secret life of Windy Hill is a story of geckos, skinks and insects. Anyone living in a pest free forest will tell you that one of the first things that happens when rats are gone, is that you start to see weta. A lot of weta. The first year of weta monitoring found just one weta in a ‘motel’ in the unmanaged control site compared to one to four in motels within the sanctuary.

Now to that lost lizard. In 2010, a Duvaucel’s gecko was found in a rat trap in the sanctuary - the first recorded sighting in 40 years. The discovery prompted a herpetological (lizard) survey and monitoring. Unfortunately no other Duvaucel’s gecko were found. Lizards in general have responded well to pest suppression, in particular the ornate skink and the Pacific gecko

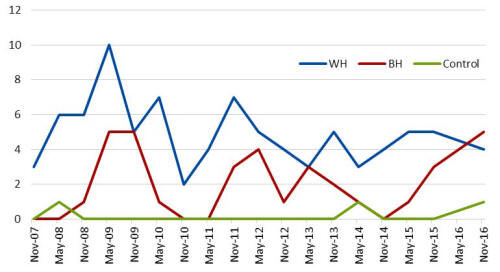

Figure 3: Ornate skink monitoring is carried out twice a year at Windy Hill (WH, Benthorn Farm (BH) and an unmanaged control site. The monitoring demonstrates the beneficial effect on this species of suppressing pests, with almost no ornate skink found in the unmanaged control site. The low point in 2010 indicates a year of severe drought

Diurnal species, such as the copper and moko skinks, appear to hold their own in unmanaged areas as they are out in the day when rats are asleep.

The other thing you notice when walking the tracks at Windy Hill is the number of seedlings. The recovery of the understory of Aotea forests, like those at Windy Hill, was affected by browsing from feral goats until their eradication in 2004. The proliferation of seedlings on the forest floor is the result of rats and kiore no longer interrupting the forest ecosystem by eating berries and seeds before they can germinate.

Predator Free New Zealand

Predator Free New Zealand is a BHAG - a big hairy audacious goal. Many people consider that Predator Free Aotea is also a BHAG. But Jude Gilbert begs to differ. She is running a real time, on the ground, research lab at Little Windy Hill, testing the technologies and methods that work best on Aotea.

The history of this small country is peppered with examples of people who simply wouldn’t take no for an answer and kept trying things until they hit on something that worked.

Predator Free NZ is targeting removal of possums, stoats, feral cats and rats by 2050. On Aotea Great Barrier only feral cats, and ship rats are present – as well kiore, mice and rabbits (not on the Predator Free NZ’s list). The combination of pests has led to species hanging on here where on the mainland they have largely disappeared. Species like the North Island kaka, kereru, banded rail, red-crowned parakeet, pateke, chevron skink, and Hochstetter’s frog.

Figure 4: Rat tracking tunnel results for 2016/17 in the pest managed areas at Windy Hill and Benthorn Bush, and the unmanaged control site compared to areas using the Goodnature A24 trap. Results to date show lower rat numbers being achieved at sites using existing methods, but that A24’s are achieving a degree of rat suppression. The project is ongoing.

The halo effect

Sanctuaries like Zealandia in Wellington talk about the ‘halo effect’ on surrounding areas – which is why you regularly see flocks of kaka over central Wellington. Tieke (saddleback) are nesting in Karori. But Windy Hill’s halo effect is economic. The sanctuary’s value to Aotea is far more than environmental.

Windy Hill has been responsible for approximately $1.5 million being added to the Aotea Great Barrier economy through wages. Windy Hill employs six people and has been responsible for taking almost all its employees off the dole and creating long term jobs that are highly valued.

Windy Hill has been responsible for approximately $1.5 million being added to the Aotea Great Barrier economy...

Gilbert is a mentor for many landowners and other sanctuaries, both on and off island. It is no coincidence that the south of the island is generating innovations like Econode.

Technology and innovation

A Great Barrier Local Board-funded a trial of Goodnature A24s is underway at Windy Hill and is yielding valuable information on the efficacy of these non-toxic, multi-kill, self-setting devices.

The data is going back to the Goodnature research and development team to try to improve the trap’s effectiveness with more than one species of rat. This has value far beyond the Barrier – a fact not lost on funders and agencies. Aotea Great Barrier, anchored by the rigour of Windy Hill’s trials could become the go-to place to pilot new technologies to eradicate rats.

Support for pest control

Over the past two years, the Great Barrier Local Board has gone into the community to explore and record how islanders feel about the ecology of the place in which they live. Gilbert was on the board when this work began, instrumental in getting it started because she knows that it all begins with a community conversation.

The Ecology Vision Project1 spent a year meeting with, and discussing, the community’s views and aspirations for the environment. Many want a pest-free island. But others are worried about the use of toxins and the practicalities, preferring instead to create a patchwork of pest free ‘oases’ where birds, plants and other taonga can thrive.

Joanne Aley, an Auckland University masters student, was also surveying landowners on the island 2. Only 2% of landowners said ‘no’ to a pest free Aotea, but another 34% were ‘unsure’. Aley’s results also showed people are much more likely to support a pest free island if they have participated in pest control activities.

These studies show just how much support there is for the protection and restoration of Aotea’s treasures.

Rangitawhiri: An opportunity for large scale community led predator control

The logical question for Gilbert and many others who share her goal of a pest free island, is how to increase participation in pest control in the south, where most people live? The opportunity exists to leverage Windy Hill’s experience, and other projects that ring Tryphena Harbour, to create an oasis in the south. It looks simple enough on paper. Join up the Windy Hill, DOC, Auckland Council, and Taumata blocks with Rangitawhiri Reserve, the Mulberry Grove community and school projects, and other private land where owners opt in, to form one large pest supressed oasis for birds, seabirds and skinks and geckos. And of course wetas!

Already there are those who say that it can’t be done, there are too many uninterested private landowners, it will be too expensive to knock down the rats and to sustain. Gilbert has heard it before. Fortunately for Aotea Great Barrier’s ecology and economy, and for New Zealand, she hasn’t let it slow her down, and shows no signs of doing so in the future.

Notes:

1 McEntee, M., Johnson, S., 2016. Aotea Great Barrier Island Ecology Vision. Weaving the Tapestry Phase 2 Report. November 2016

2 Aley, J., 2016. Environmental and pest management attitudes of Hauraki Gulf Island Communities. Thesis for the MSc Biological Science (Biosecurity and Conservation) University of Auckland 2016.

Environmental News Issue 38 Spring/Summer 2017