Rakitu: Where the Light meets the Sky - A fascinating history - and a future as an eradicated sanctuary?

by Kate Waterhouse

Environmental News Issue 29 Summer 2012

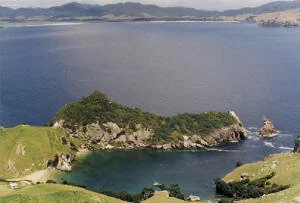

The Cove on Rakitu (Arid) Island, is the only sheltered anchorage on the east coast of the Barrier. Arriving by sea, the entrance is hard to spot, with cliffs towering on both sides, and clefts reaching far back and even right through the rock. Once inside the cove there’s a sandy beach and ample anchorages. On a fine day, there are few more beautiful places to be.

A hiker ascends the slopes above Arid Cove Photo: Mike Waterhouse

Rakitu’s isolation, size, history and spectacular landscape give the island the potential to be an extraordinary place for conservation and co-management with iwi. The island was the home of Rehua, founding ancestor of Ngati Rehua, who was killed there by his rivals. The light from his burning whare is said to have been reflected from the rocks of Hirakimata. Rakitu was first sold to Europeans in 1883 and has been farmed and grazed for 120 years. Currently the subject of treaty negotiations, the island has been leased to its former owners since 1993. The lease expires in 2013, and both DOC and Ngati Rehua have shown support for eradicating rats to create a new island sanctuary. Rodney Ngawaka of Ngati Rehua describes a future for Rakitu as the Tiritiri Matangi, the jewel of the outer Hauraki Gulf.

A secret interior

The island is fortress-like, with cliffs rising 180 metres sheer from the sea in places. But invisible from the Barrier is the grassy, gently sloping interior valley which splits the island in two. There are three pa and dozens of dwelling sites, storage pits, drainage ditches, middens and shelter rocks, providing evidence of year-round Maori occupation for 300 years. There’s also the remains of a whale- watching station abandoned in the 1950s, and three houses and a woolshed used by the Rope and Foster families and their caretakers. This central farmed area separates the remaining original forests and kanuka on the high ground to the east and west.

Endemic birdlife on the decline

“Within 130 years the endemic bird fauna of Rakitu has been reduced to resemble that of the North Island mainland, through pasture development, vegetation succession, browsing of forests by stock and ship rat predation and competition for food”. This was the sad assessment of Beauchamp, Blick and Chambers in their 2002 report to DOC on the Status of weka and other birds on Rakitu (Arid) Island.

The baseline research on Rakitu’s biodiversity was carried out by the Offshore Islands Research Group, in 1981. Earlier observations were made by, Hutton and Kirk in 1867, and Bell and Braithwaite in the early 1960s. By 1981, whitehead, käkäriki and tomtit had all died out. Pied shags were breeding then, but few have been recently recorded. In 2002 Beauchamp et al. noted that since 1981 bellbirds and pipits had also died out, and kaka were not seen (although it is assumed they are visitors). Kereru were estimated at 10 birds.

Tui, morepork, grey warblers, kingfishers, fantails, silvereyes, shining cuckoos, and little blue penguins are all still present, as well as introduced pasture birds, paradise shelducks, spur-winged plovers and welcome swallows. The introduced wekas seem to be thriving. Pateke have been observed breeding with up to 20 birds, assumed to come and go from Okiwi.

Just one mammalian predator – the ship rat rattus rattus appears to have been responsible for the extinctions; in 1867 Hutton and Kirk encountered a party of mutton birders from Aotea who said the birds had declined since the arrival of ship rats. Cats were reportedly once present, but apparently died out. In 1998 Phil Todd and colleagues from the Great Barrier field office undertook a trapping programme to assess rodent and cat numbers on Rakitu. Only ship rats were caught; no cats, kiore or mice.

A missing link in the chain of seabird islands

The absence of seabirds from our forests is perhaps one of the least visible and greatest losses of biodiversity in New Zealand. Clear evidence for this exists on Hauturu (Little Barrier) where more than a million Cook’s petrels now breed, following the eradication of cats, rats and finally kiore in 2003.

Rakitu sits in a prime location for seabirds. Excluding gulls, terns, waders and shags, 31 oceanic seabirds have been recorded from Great Barrier’s coastal waters. Grey-faced petrels, cooks petrels and diving petrels, were plentiful on Rakitu in pre-European times and were a source of food for Maori. White-faced storm petrels, black petrels and fluttering and little shearwaters also breed nearby and may have been present historically, but by 1867 Hutton & Kirk reported grey faced petrels were scarce. In 1981 Cooks petrels were heard overflying the island at night but only empty burrows could be found. Coastal birds such as shags and gannets, Caspian and white fronted terns are still present, but due to the combined impacts of rats, weka and stock damaging burrow sites, so far as is known, no seabirds now breed on Rakitu.

Cooks petrel could be enticed back to breed on Rakitu.

As the Offshore Islands Research Group pointed out in 1981, Rakitu should have nesting seabird colonies. To the north, the rat-free Poor Knights host 9 species of petrels. To the South lies Cuvier Island, again without rats and with huge seabird colonies. Like Rakitu, the nearby Mokohinau islands were also farmed before the eradication of rats in the 1990’s. Seabird expert Chris Gaskin points out there are now 7 species of petrels and shearwaters breeding on the Mokohinaus group and these islands have the highest diversity of seabirds in New Zealand. Experience at Tawharanui 4–5 years after eradication of predators shows seabirds can be attracted back. There Gaskin says, four target species, including Cook’s petrel turned up after speakers were used to play calls to entice birds to land. He sees potential for this on Rakitu, combined with the use of artificial burrows, as on Raoul Island, Tiritiri Matangi and at Tawharanui.

Reptiles in jeopardy

In 1981 there were at least five reptile species on Rakitu – the Pacific gecko, common gecko, copper, ornate and moko skinks. This survey has not been repeated but low numbers of lizards and skinks may indicate ongoing attrition due to rats and possibly weka.

A rat-free Rakitu would have great potential for reptiles. Monitoring on the Hen and Chickens group includes Hen Island where kiore were not removed. Other predator-free islands in the group show the dramatic recovery that reptiles, including skinks, geckos and tuatara can achieve where young are not taken by rats or cats. Evidence is also to be found on Great Barrier, where Little Windy Hill sanctuary has enjoyed a resurgent reptile population. This includes the rediscovery of Duvauchelle’s gecko, which is thought to have held out on the cliffs while rats prevailed in the bush. Although chevron skinks have not been found on Rakitu, the Oligosoma (chevron skink) Recovery Group has highlighted Rakitu as a potential release site for this iconic Barrier species if rats are eradicated in future.

Original vegetation hangs on

Rakitu is larger than Tiritiri Matangi at 245ha, but has more intact forest cover: In 1981 about 50% was in grass, 25% kanuka and 25% original bush. The sides of the central valley and the ridgelines are now covered in mature kanuka, while pohutukawa and taraire dominate the original forest with kohekohe, tawaroa, nikau and a few isolated kauri and miro. Also present are rewarewa, puriri, tawapou, karaka, maire, and mahoe. Large leaved forms of rangiora and kawakawa also occur. Of the 321 plant species recorded in 1981, 240 are native, making Rakitu highly diverse for its size. The lichens and seaweed floras are also diverse.

Following a long history of burning and farming, stock were removed from Rakitu in 1994. Some paddocks have returned to gorse and manuka but DOC have managed weeds such as pampas grass. Some steep gullies and cliffs were not reached by stock, resulting in the preservation of some plants not found elsewhere, notably koru (colenso physaloides). Halema Jamieson describes koru as a Hydrangea-like plant which prefers shaded habitat and produces spectacular purple flowers in late summer. The remnant forest patches represent a crucial seed source for future restoration.

Koru (Colensoa physaloides) in flower. Photo by Halema Jamieson

A swampy area formerly existed at the head of the central valley but by 1981 raupo had disappeared and other swamp plants were eaten down by cattle. The swamp and stream were home to kokupu (native fish), eels, pateke and paradise ducks.

Some cattle were recently reintroduced by the lessee, to reduce fire risk to buildings. Regeneration in Te Paparahi following the eradication of goats and cattle, shows forested areas will recover once browsing animals and rats are removed. Aside from predation of birds and eggs, rats also take seed and slow regeneration of some tree species. Large areas of the centre of Rakitu remain in grass and will require intensive planting to support natural revegetation.

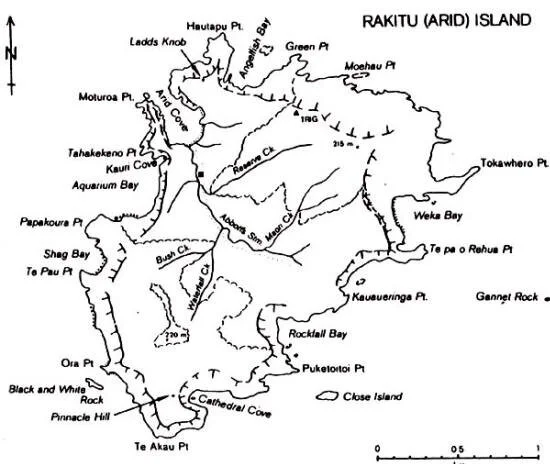

Rakitu from Tane 1982 map

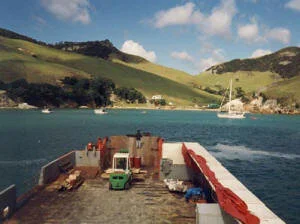

The Subritzki Shipping barge coming into Arid Cove to load stock c.1994. Photo: Mike Waterhouse

The Tiritiri Matangi story

Comparison of Rakitu with Tiritiri Matangi is both interesting and useful. After 117 years of farming and burning of grass and forest cover, Tiritiri Matangi has been intensively replanted, starting in 1984. Only 6% of the island’s 220ha was original forest at the time reforestation began. These few patches included large pohutukawa trees and were important seed sources for the revegetation which followed.

Tiritiri Matangi is one of the most successful community-based conservation projects in the world, creating a home for some of our most endangered birds. The transformation of Tiritiri Matangi has taken more than 20 years, thousands of volunteers and funding from numerous national bodies and private donors. Between 1984 and 1994, 283,000 trees were planted covering 60% of the island. The sanctuary is a partnership between DOC and the community, through The Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi, a non-profit community conservation organisation. This support group was formed in 1988 to continue the planting programme and work in the on-site tree nursery.

Looking down into Arid Cove with Whangapoua in the distance. Photo: Mike Waterhouse

The main focus on Tiritiri Matangi has been to re-establish the forest ecosystem, complete with native birds and reptiles. Bellbirds and tui had hung on, and red-crowned kakariki were brought over as early as 1974. Tieke (saddlebacks), mohua (whiteheads), pateke (brown teal) and takahe were trans-located over the course of 10 years, prior to the eradication of kiore in 1993. After this, the programme of translocations accelerated to include little spotted kiwi, kokako, hihi (stitchbird), fernbird, riflemen, tomtits, tuatara, Duvauchel’s gecko and shore skink. Forty percent of the island has been left in open grassland for species such as Takahe, and humans, which prefer open habitat. In a sense, as one specialist remarked to me recently, Tiritiri Matangi is effectively a zoo. But it is also a place where everyone can see a part of New Zealand which has largely disappeared elsewhere.

Out damn rats!

Eradication of rats is likely to involve aerial drops of broadificoum followed by monitoring. At least 3 species of birds – pateke, banded rail and weka, would need to be captured and removed during this process because they are likely to feed on dropped baits. Experience on Ulva Island indicates more than 90% of weka died after a poison drop.

Rakitu is too far from the mainland of Aotea for even the most determined ship rat – their swimming range is approximately 1km and the island is 2.5kms from Harataonga and 3.5kms from Waikaro Point. The main risk of reinvasion will be from stowaways on visiting boats or floating debris. To ensure any reinvasion will be detected and managed, regular monitoring using biosecurity sentry stations will be required, employing live-on rangers or volunteers.

The vexed weka question

Weka are not endemic to Rakitu, ten birds were introduced in 1951 by wildlife officers concerned about the reduction of North Island weka numbers elsewhere (they are a separate species to the more plentiful South Island weka). This concern proved well founded, and the national Weka Recovery Group now recognise that the Rakitu population could be used for trans-location. In 2002 Tony Beauchamp estimated there to be 240 weka on the island. Weka are thought to have had a deleterious effect on seabirds, land snails, lizards and skinks, but to what degree is not known because of the simultaneous effects of ship rats. If weka need to be removed to avoid mortality during a rat eradication, two questions arise: where should they be removed to; and should they be re-introduced back onto Rakitu, or permanently trans-located elsewhere (such as to an existing weka sanctuary island – Kawau, Mokoia or Pakatoa)

Restoration vs island arks

There is a growing realisation that the remaining ecosystems of mainland New Zealand are under siege by introduced mammals. The network of sanctuary islands, particularly in the Hauraki Gulf, are the last and possibly only hope for the survival of many bird species, such as tieke, kakapo, takahe, hihi and kokako. In theory, all species present on Tiritiri Matangi could be introduced to Rakitu, but there are a number of caveats. Assessment of adequate quality habitat to support kokako, saddleback and hihi has not been done. Extensive planting of feed-trees and installation of nesting boxes has taken place for saddleback and hihi on Tiritiri Matangi because of poor habitat. Little spotted kiwi, introduced to Tiritiri Matangi, may never have been present on Rakitu or Aotea and could present a risk to lizards and skinks.

Rakitu has a head start in many ways – more intact forest cover and seed sources, and local (on Great Barrier) expertise in eradication, regeneration and translocation. On Great Barrier, kakariki and tomtits are at very low numbers. Relocating the survivors to Rakitu could help them, although kakariki could easily return to a rat-free Rakitu without human help. Bellbirds are known to visit Okiwi from Hauturu and may also find their way across. Then there are the seabirds which may return naturally or need to be enticed; and reptiles, such as chevron skinks, which are threatened elsewhere, or others which may yet be surviving on the cliffs.

Partial restoration can be achieved quickly on Rakitu with removal of rats, followed by reintroduction of species such as käkäriki and tomtits. Bellbirds and mohua could be brought in from Tiritiri Matangi, where they are numerous. Use of speakers to entice seabirds back is straightforward, but removal of weka is not. Beyond this, other species which may have been present historically include riflemen, saddleback and hihi and these could all be released. Yet other species have and will be proposed: takahe (for the grasslands) and tuatara.

Cash and carry

Any replanting programme will require an on-island or Aotea-based nursery and volunteer labour. Managing volunteer and visitor programmes will be a major challenge. Protecting the island from reinvasion by boat-borne predators is a considerable commitment. Budget pressures on DOC mean funding is hard to come-by. A financially and logistically sustainable solution is needed.

Treasure Island

There seems to be strong support amongst iwi and within DOC to eradicate rats and restore Rakitu to something like its original state in terms of habitat and biodiversity. The success of the project will depend on a collective will to work together to conserve what remains and restore what has been lost. The challenges ahead lie as much in agreeing on principles and securing funding, as in the practical difficulties of access, eradication, translocation and biosecurity.

Whatever the solutions, surely they must reflect Rakitu’s deep and unique significance for Ngati Rehua, its size, isolation and variety of habitats. It is an extraordinary presence in a chain of seabird islands stretching from Northland to the Bay of Plenty and in a growing network of predator-free islands of the Hauraki Gulf. It is a treasure island, a taonga, of that there is no doubt.

REFERENCES & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Grateful acknowledgement is given to Rodney Ngawaka, Halema Jamieson, Rebecca Gibson, John Ogden, Chris Gaskin, and Tony Beauchamp for their input and guidance in the preparation of this article. References used include:

State of the Environment Report for Great Barrier Island (GBICT 2006)

Reports of the Offshore Islands Research Group trip to Rakitu (Arid) Island, New Year 1980- 1981: Tane 28, 1982 (PJ Bellingham, JR Hay, RA Hitchmough, J McCallum, FJ Brook, EK Cameron, AE Wright, Hayward B & GC, et al).

Great Barrier Island Wildlife Survey, Tane 27, 1981, CC Ogle

Raising the prospects for a forgotten fauna: a review of 10 years of conservation effort for New Zealand reptiles. Biological Conservation, D Towns, C Dougherty & A Cree (2001)

Status of weka and other birds on Rakitu (Arid) Island, AJ Beauchamp, AJ Blick and RC Chambers (2002), report

Department of Conservation, Great Barrier Field Office archives

Department of Conservation trip reports 2001-2011, Great Barrier Field Office archives

Tirtiri Matangi: A Model of Conservation, Annie Rimmer, Random House 2004

Websites of The Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi and Department of Conservation.