Lord Howe Island moves closer to rat eradication - The Aussies intend going where others fear to tread

Edited by Judy Gilbert and David Speir

Environmental News Issue 29 Summer 2012

Like New Zealand and other geographically isolated islands of the pacific, many of Lord Howe Island’s endemic species of birds, reptiles and invertebrates has been decimated by the aggressive and highly competitive European mouse and the black (ship) rat. Like Great Barrier Island, Lord Howe is inhabited by people, visited by tourists and has farmed animals and domestic pets. The Aussies however are intending to boldly go where others have yet to tread – they intend to eradicate mice and rats from Lord Howe.

Planning for the eradication of rodents from Lord Howe Island has progressed with financial support from the Australian Governments Natural Heritage Trust, the NSW government, the Foundation for National Parks and Wildlife, and the Lord Howe Island Board. Recently the Board has received all the funding to implement its proposed rat and mice eradication programme.

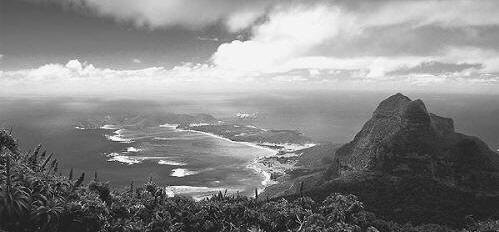

The Lord Howe Island group is 760km north-east of Sydney and the group consists of Lord Howe Is (1455ha), Roach Is (15ha), Mutton Bird Is ( 4.5ha) and Blackburn is (3 ha) plus smaller rocks and islets. Great Barrier, by comparison, is 28,000 ha including all its outlying islands, islets, and rock stacks. The resident population on Lord Howe is around 350 in approximately 150 households.

The outstanding natural beauty, together with its diverse flora and fauna, was recognised in 1982 when the island group was made a World Heritage Site. Tourism is one of two major sources of income with about 16,000 visitors each year (Great Barrier is estimated to have about 28,000 visitors a year.) Visitor numbers on Lord Howe are regulated to a maximum of 400 on island at any one time. The growth and export of kentia palms provide the other main source of income for the islanders with the Lord Howe Board operating a nursery that exports 2-3 million palm seedlings annually.

The first mice reached the islands in the 1860s followed by ship rats in 1918. Within two years the rats were so widespread that a bounty system was implemented to try and control them. The environmental effects were noticed immediately with one local commenting in 1921 “one can scarcely imagine a greater calamity in the bird world than this tragedy which has overtaken the avifauna of Lord Howe Island”.

Rats are implicated as the “key threatening process” in the extinction of five species of endemic birds, two species of plants, and at least 13 species of invertebrates with another 13 species of birds, two species of reptiles, 51 species of plants, and numerous invertebrates now threatened.

Kentia palm seeds are prim rat diet on Lord Howe Island.

The Lord Howe Island (LHI) Board embarked on eradication planning in 2006 following a study in 2001 which concluded that the eradication of rats and mice was technically feasible. A cost benefit study in 2003 demonstrated that costs of the eradication would be quickly offset by discontinuation of the current rat control programme and increased yields of commercial palm seed. If undertaken, Lord Howe and its smaller islands would be the largest, permanently inhabited island, on which the eradication of ship rats and mice has been attempted.

Control or Eradication

There have been attempts to control rats on LHI since about 1920. Currently control includes protection of the kentia palm over about 10% of the island using about 1000 bait stations replenished 5 times a year with anticoagulant baits. Brodifacoum is used around the island’s commercial palm nursery and by residents in and around residences. This control effort currently costs the LHI Board about A$65,000 per year.

The topography of Lord Howe contains rugged bush clad peaks as well as lowland pasture -very similar to Great Barrier Island.

The increasing frequency and success of island eradication programs and the increasing costs and limited success of control on LHI led the Board to examine the feasibility of eradicating ship rats and mice from the islands.

In 2003 the LHI Board reviewed the risks and constraints around eradication and assessed the various costs and benefits involved. This report demonstrated the financial benefits if rats were eradicated and also acknowledged the biodiversity benefits. An eradication would thus provide overall benefits greater than can be achieved through the current control programme.

A draft plan for the eradication was developed in 2009 in consultation with expert planners and practitioners from around the globe together with the LHI community.

The challenges include: (1) the complexities of targeting two pest species; (2) the existence of threatened endemic species that are susceptible to poison; and (3) the presence of a resident human population, a well developed tourist industry, domestic animals and livestock.

The plan recognises that:

• Eradication rather than ongoing control is the most effective long-term option;

• The impacts of rodents on LHI are significant and ongoing;

• Eradication is feasible using current techniques without unacceptable risks to non-target species and humans.

The operation will utilise the cereal based Pest-Off Rodent Bait containing Brodifacoum at the concentration of 20ppm. The primary method of bait application will be through 2 aerial broadcasts 10-14 days apart, with hand broadcasting or bait stations used in areas not suitable for aerial application, such as in the settlement area or where livestock are present.

Mitigating Potential Impacts on Threatened Species

Brodifacoum has been used effectively to eradicate rodents on islands and in fenced sanctuaries worldwide more than 200 times. It does however, affect some non target species and for LHI an evaluation of the potential risk to these species has been carried out and been given prime consideration.

Lord Howe's iconic woodhen - focus of the mitigation effort.

Birds – There are four endemic species that survive on LHI: the LHI woodhen, the LHI pied currawong, the LHI golden whistler and the LHI silvereye. Since 2007 the numbers and habitat of these species has been carefully monitored. From trials using non-toxic baits it is known that the woodhen (similar to our weka) and the currawongs would be at risk of taking bait or secondary poisoning from eating poisoned rats. To minimize the potential impact at least 85% of the woodhen and 50% of the currawong population will be placed in captivity for the duration of the risk.

Captive management will require the construction of a precision built, rat-proof enclosure for woodhen and aviaries for other species. The surrounding areas will be baited before and after the main eradication to ensure they do not harbor any rats.

Reptiles and Mammals – Two species of native reptiles are present on Lord Howe and its nearest neighbour Norfolk Island: LHI skink and LHI gecko. The insectivorous diet of the species exposes them to the risk of ingesting Brodifacoum if they feed on invertebrates that have ingested the bait. However, the risk of secondary poisoning is low because of the different blood chemistry of these reptiles and because the baiting will take place in the winter when reptiles are less active. There have also been no wide-spread deaths of reptile species following rodent eradications. In many instances the removal of rodents has resulted in a substantial increase in the abundance of reptiles. For example the number of skinks on Korapuki Island increased 30-fold within five years of rats being removed.

The only extant native mammal on LHI is the large forest bat, a species that is common throughout much of southern Australia. It is insectivorous and is therefore considered to be at low risk of poisoning.

Invertebrates – The LHI group has numerous endemic species of terrestrial invertebrates and predation by rats is regarded as a significant threat to many. Only one species is considered to be at low risk from bait, the Lord Howe flax snail, so a number of snails will be collected and housed in captivity for the duration of the baiting programme.

Effects of Human Habitation on Eradication Design

A human population and their associated pets and livestock raise issues rarely encountered on other large islands where eradications have occurred. However, modifications made to ensure the safety of the community need not jeopardise the success of the operation.

Currently there are 100 beef cattle and a herd of 14 cows provides milk for local consumption. There are also 3 horses, 12 goats, and 300 chickens on the island. Pigs are prohibited. Beef cattle will be destocked through slaughter during the two years leading up to the eradication. Owners will either be compensated financially or given replacement stock brought to the island when the breakdown of bait is complete. Most owners of stock have indicated their willingness to cooperate in this process. The dairy herd as well as goats and horses will remain on island throughout the operation, with animals confined to a small paddock connected to the existing milking shed by a narrow race. Confinement will extend until baits disintegrate. Cattle proof bait stations will be placed within the 30 m buffer zone of this paddock.

All poultry will be eliminated from the island at least a month before the eradication and be replaced after the eradication. Poultry owners will be compensated for lost egg production.

There are approximately 48 domestic dogs on LHI. Cats are prohibited. The option of removing dogs to kennels on the mainland will be available for all dog owners at no cost. Given the current high use of poisons in the settlement are now, most dog owners are aware of the risks to dogs, nevertheless an education programme will be implemented to advise island residents of the potential risks to pet dogs and how to avoid them. Any cases of poisoning will be treated locally.

Community baiting strategies The proposed operation on LHI will utilise a combination of aerial, and broadcast, and bait station techniques in order to deal with issues associated with human habitation, public concern about aerial baiting in a residential area, and to protect potable water storages. Each property will have a negotiated ‘property action plan’ with agreements with the LHI Board about effective and safe actions on each property. These plans will detail: how and where the bait will be distributed on each property; methods to control rodents in the lead up to the eradication; management of pets; procedures to ensure the health and safety of all family members; and procedures to dispose of compost and food waste before and during the eradication.

The black rat, a very successful stowaway.

Biosecurity

A biosecurity strategy current exists for LHI. Additional measures needed to ensure that rodents are not reintroduced once they have been eradicated include; improved checks of cargo before departure from the mainland; in-transit checks of sea freight; pre-landing inspections of the cargo vessel and private yachts; arrival inspections of all aircraft and passengers using trained detector dogs.

Socio-political planning

Several community meetings and focus groups have been held on LHI to inform the community about the need for an eradication, how it would be undertaken, and when it is likely. The meetings outlined environmental benefits of rodent eradication, along with the potential flow-on effects for tourism. Explanations were made of the operations’ best practice and how it drew on the wealth of previous successful operations. The potential risks were identified and the contingencies built into the planning process to ensure risks were mitigated. What was also explained was the continued risk to children, non-target species, livestock and pets with continued use of baits over time.

A survey on LHI in in 2009, approximately 15 months after the commencement of consultation, indicated that 96% of the 126 respondents agreed with the need to eradicate the rats from the island. Many concerns raised by the community can be addressed through appropriate information. Topics include ; (1) impacts of rodents on islands; (2) the benefits of rodent removal; (3) the impacts of baiting on non-target species; (4) the choice of poison; (5) the methods of bait dispersal; (6) human health risks; (7) risks to the marine environment.

Where is it up to now?

Currently the project managers are preparing a brief to engage specialist consultants to:

(a) Provide strategic advice on the approach to inform, consult and engage the community (and other relevant individuals and groups) on the development and implementation of the Rodent Eradication Plan.

(b) Assist with the establishment of a Community Liaison Group and provide professional facilitation of the initial 3 meetings of the group.

(c) Provide Draft Communication/ Community Engagement Plan in consultation with CLG for review by Steering Committee.

The GBI Trust is keeping in close communication with the project as its complexities are similar to those that would be experienced by Great Barrier if it were to undertake a similar type of eradication.

If the eradication of rodents from this World Heritage Site can be achieved it will arguably be one of the most significant management actions undertaken for threatened species conservation in Australia and provide a blueprint for other inhabited islands keen to restore their biodiversity.

*Extracted from the paper “Rodent eradication on Lord Howe Island: challenges posed by people, livestock, and threatened endemics” By I.S.Wilkinson and D. Priddel.