Caulerpa Crisis: Need to Know

KATE WATERHOUSE (Chair, Aotea Great Barrier Environmental Trust)

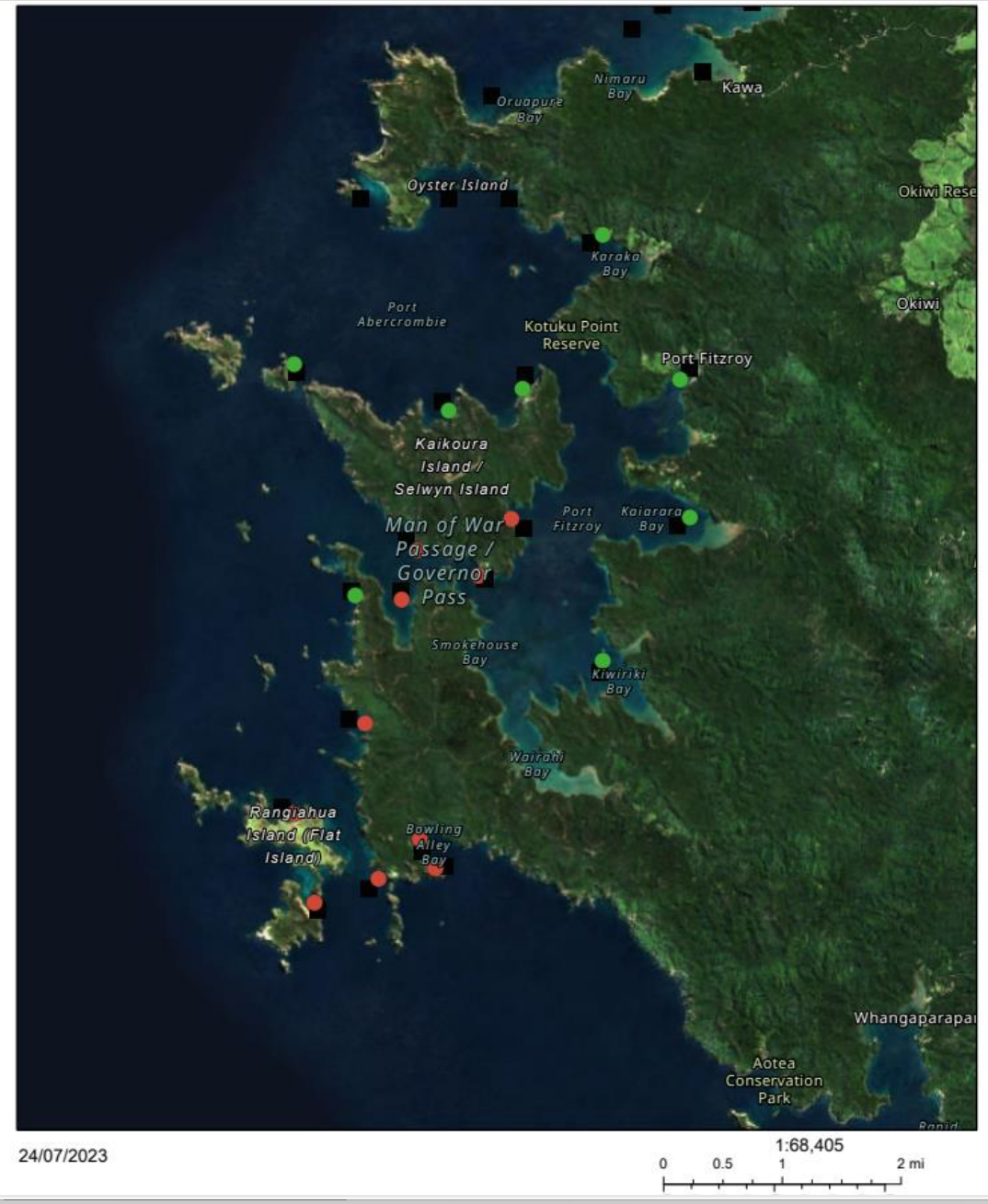

ICYMI: the worst marine pest to ever reach NZ, the fast-growing exotic caulerpa seaweed (aka “caulerpa”), is established from Tohorā/Rabbit Island to Motu Kaikoura – and it won’t stop there.

Why you probably should be worried:

Caulerpa can grow at 3cm a day and from a fragment as small as 1cm and looks to be thriving in our waters between 6 and 40m – possibly because they are very clear and have low levels of sediment. It has likely moved here on anchor chains, fishing gear or currents.

New infestations are certain - in July NIWA divers found further infestations along the west coast as far north as the entrance to Port Fitzroy, well outside the three Controlled Areas. The CANs in place for 2 years will have stopped some boat/fishing gear spread but now there’s a bigger problem.

The Caulerpa family of seaweeds are found all over the world but it is the non-native ones (bred for aquariums) which are toxic to our fish, smother other seaweeds, limit the fish species, seaweed and other fauna present and cover the holes of crayfish/koura, growing on and around scallop beds and other shellfish.

Killer seaweed: quite literally this species can suppress most or all other marine life where it establishes. In the Mediterranean and in California infestations have led to a 50% reduction in fish, with knock on effects of similar magnitude on tourism and the commercial and recreational fishing sector.

There is no doubt what will happen if caulerpa is left to grow here. It means the permanent localised loss of crayfish, scallops, mussels, paua and an unknown number of other fish species from caulerpa sites, and any species, whānau, communities or businesses which depend on them. It will not stop unless we stop it. NIWA indicate Caulerpa species could establish from North Cape to East Cape if not detected and controlled.

Is there any good news?

Yes. The good news is there is a LOT of experience to draw on from California where caulerpa has been successfully removed and eradicated from multiples sites. These experts stress the need for early detection and control, site by site. So, even with the mass growing off Okupu, small new sites can still be dealt with, one by one.

In August, Ngāti Manuhiri (now fighting caulerpa at Kawau) brought Rachel Woodfield, Robert Mooney, Seth Jones and Eric Munoz out from California to share their experiences on how to get rid of it, under the umbrella of Te Wero Nui. They stressed the need for rapid response, mindset of “get rid of it!”, coordination, and maintaining the funding.

Their core samples of the seabed showed the massive drop in biodiversity under caulerpa masses – even in bare mud, there was more life than in a caulerpa meadow. They also acknowledged that people could be uncomfortable with suction dredging and mats killing other sea life but that caulerpa takes over the sea if unchecked, and sea life disappears anyway. All caulerpa species are now banned in California.

So, there are four “must do’” to stop the spread – and the Californians are adamant we should be doing all of these at once:

Locate it – methodical surveillance along underwater transects by divers, snorkelers, underwater drones, and by community reports. This is crucial because early in its growth cycle caulerpa is sparse and patchy and can be removed by hand with training.

Exclude anchoring boats and fishing gear from known sites and educating boat owners on identifying it and cleaning/disposal. Once caulerpa forms dense mats, like at Okupu, boat anchoring and fishing are high risk because fragments can be carried by boats on anchors and gear spreading to new locations.

Remove it – either by hand if small, or by covering it under thick weighted down tarps like pond liners (it gets no light so it dies), and by diver assisted suction dredging (MPI trial starting in Tryphena this week). Other methods may be found (let’s hope so!) but these are the ones proven to work so far.

Monitor the sites long term – to detect and prevent regrowth in sites that have been treated, and to detect spread to new sites, trained local surveillance crews keep going back to check it’s gone, helped by volunteers and members of the public.

It’s a crisis already and an El Nino summer will make it worse

Caulerpa will spread from the established masses between Bowling Alley Bay and Tryphena when fragments break off and move elsewhere on currents or equipment. The high risk of spread gets higher with the upcoming El Nino, likely south west winds sending more boats to Aotea than has been the case for the last 3 years. There is a very grave risk that this increase in boats will spread caulerpa to more Barrier anchorages and fishing spots, and beyond. Plus, it grows faster in summer.

El Nino will increase ocean temperatures, which is good for Caulerpa and bad for kelp forests. Kelp forests keep light low and may stop Caulerpa growth but can die off if the sea gets too warm.

Caulerpa Infestation at Okupu Bay (Image: Irene Middleton (NIWA))

So what needs to happen next?

Some of the northern sites in the Broken Islands may be new and sparse enough to remove now – if we’re quick. To stop the spread, a locally based Aotea Caulerpa project needs to start work within 1 or 2 months to precisely map and begin removal of Caulerpa, site by site.

We need to be sure that all whānau, community and visitors to Aotea clearly understand how bad this is, including the impacts of the infestation and what can be done to stop it.

Extending restrictions also has to be on the table unfortunately. This is not just about Aotea—there are cultural, ecological and economic impacts on the entire north east coast of Aotearoa of uncontrolled caulerpa getting away here.

Finally, securing sufficient funding for a sustained response over three years is critical.

THE Government needs to do way better

Despite NZ having one of the largest ocean territories in the world, MPI has minuscule budgets for marine biosecurity response. It receives a fraction of the funding of other MPI priorities such as Kauri Dieback, Myrtle Rust ($20m spent on research alone) and Mycoplasma bovis ($800m+ on attempted eradication). The spill of the Rena reportedly cost $130m and cleanup was not questioned. Because caulerpa is growing out of sight and out of mind it is more dangerous than any oil spill. Inexplicably, no National Management Plan has been put together to prevent the spread in New Zealand.

MPI staff are between a rock and a hard place, struggling to respond to the needs of iwi, hapū and communities at multiple sites for more support. A new removal model that is locally led, and a major increase in investment for the next 10 years are desperately needed. Conservatively, $200m has been requested by iwi in three of the infested rohe including Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea Trust. So far only the Green Party has committed to funding local response and increasing marine biosecurity spending and legislation to match the risks.

Auckland Council and central government were warned in 2002 by Californian experts that Caulerpa strains would reach New Zealand and could be devastating. No action was taken to prevent the import and sale of Caulerpa seaweeds bred for the aquarium industry (which has been a source of incursions overseas – from homes and super-yachts).

MPI have started suction dredge removal trials here this week and they have committed to a further “conversation” with the Minister of Finance if these are successful. This is an example of the slow and linear approach to date. There is no rational reason to wait for the outcome of these trials to set up and Aotea Caulerpa crew. Other iwi and communities have already started more detailed surveillance to detect and remove it at Kawau, Waiheke and in Bay of Islands sites. This is what must happen on Aotea.

Now is the time to make it a political issue

MPI and Auckland Council representatives have said privately that funding Caulerpa is “a political decision”. Both are under severe budget pressure and both are already reallocating existing budgets to ensure some activity can occur. But it’s nowhere near enough.

The Hauraki Gulf Forum recently completed a natural capital evaluation of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, which values the Gulf at $100 billion (yes, really). Northern New Zealand and especially the Te Moana Nui o Toi/Tikapa Moana is a global hotspot for whales, dolphins, manta rays, seabirds and marine biodiversity and will at last soon see the establishment of new marine protected areas. Above all, it feeds and nurtures us.

It is hard to understand why local and central government have not invested in the health of the sea. But surely no party will want to be associated with the severe economic, cultural and social consequences of this invasion if it is left uncontrolled. Okupu shows what will happen if nothing is done, and the Californian experience shows we still have time to stop the spread.

What can you do?

Make some noise and use your vote: it’s a month until the election and so far only the Greens have made a commitment to fund local Caulerpa response on Aotea and increase funding for marine biosecurity. Without this our waters will be overtaken within years.

Ask Auckland Council to allocate funding in the upcoming 10 Year Budget or “LTP” for local Caulerpa response on Aotea and educating boat owners about the risks. Our Local Board (Izzy and Chris) are leading the charge, but direct approaches to the Mayor Wayne Brown, the Chair of the Environment, Planning and Parks Committee Richard Hills, and to Councillor Mike Lee will add more weight.

Support of the next phase of the Aotea response once plans are more developed. If you have diving, snorkelling, underwater drone or GIS skills, and local knowledge you’ll be needed.

For more detailed information and sources please go to our Caulerpa Response webpage.

Thank you to Izzy Fordham, Barry Scott, members of Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea, Glen Edney, Thomas Daly, Hannah Smith, Revive Our Gulf, the Waiheke Marine Project, Te Wero Nui, and MPI and Auckland Council staff for assistance with this article and on the emerging Aotea response.